Zhou Huijun is certainly a master calligrapher in contemporary China, but the puzulling fact is that she is hardly known by anyone nowadays. She is perhaps due to her low-key personality.

Zhou Huijun, a native of Zhenhai of Zhejiang Province, was born in December 1939. She was the vice-chairman of China Calligraphers’ Association, vice-chairman of Shanghai Federation of Literary and Art Circles, and chairman of Shanghai Calligraphers’ Association. Currently she is the honorable chairman of China Calligraphers’ Association and Shanghai Calligraphers’ Association.

.

Zhou Huijun, a native of Zhenhai of Zhejiang Province, was born in December 1939. She was the vice-chairman of China Calligraphers’ Association, vice-chairman of Shanghai Federation of Literary and Art Circles, and chairman of Shanghai Calligraphers’ Association. Currently she is the honorable chairman of China Calligraphers’ Association and Shanghai Calligraphers’ Association.

.

中国当代书法家中,周慧珺肯定是大师级的书法家,可是令人不解的是,整个书坛似乎知道她的人好像不多。这可能是她为人低调的缘故吧。

Zhou Huijun, a native of Zhenhai of Zhejiang Province, was born in December 1939. She was the vice-chairman of China Calligraphers’ Association, vice-chairman of Shanghai Federation of Literary and Art Circles, and chairman of Shanghai Calligraphers’ Association. Currently she is the honorable chairman of China Calligraphers’ Association and Shanghai Calligraphers’ Association.

Zhou Huijun, a native of Zhenhai of Zhejiang Province, was born in December 1939. She was the vice-chairman of China Calligraphers’ Association, vice-chairman of Shanghai Federation of Literary and Art Circles, and chairman of Shanghai Calligraphers’ Association. Currently she is the honorable chairman of China Calligraphers’ Association and Shanghai Calligraphers’ Association.

Zhou was brough up a merchant family which valued education and learning. She learned Chinese calligraphy since she was young. However, her father who loved Chinese calligraphy and painting, did not pay too much attention to her study, so she was given a free hand to study what she liked. It was unfornate that she had rheumatoid arthritis at very young age which caused her joints to become swollen, stiff and painful. This had affected her learning of calligraphy. However, this did not deter her; instead it motivated her to work harder.

In 1974, Zhou published a book on ‘Calligraphic Works on Running Script – Selected Poems by Lu Xun’. The book was re-printed four times within a year and more than a million copies were printed. This has set a new record for the highest initial print run of any Chinese calligraphy book. Some readers commented that after reading the book in detail, it was hard to believe that it was written by a weak lady who was seriously ill. Zhou had finally overcome the adverse conditions and achieved great success in her works.

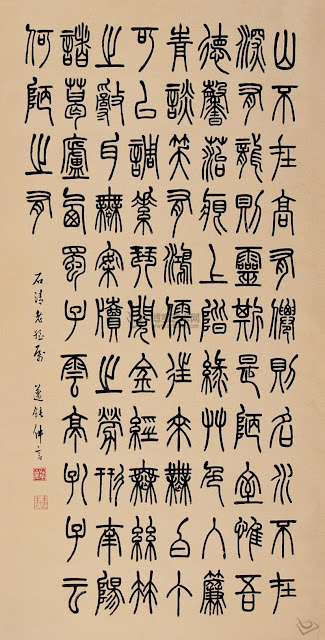

In learning calligraphy, her father wanted her to start with the Zhao stye (the calligraphy of Zhao Mengfu), but she was only fond of Mi Fu’s calligraphy. In 1975, Zhou entered the Shanghai Chinese Painting Academy and became a professional calligrapher. Like a thirsty steed dashing to the spring, she started her Chinese calligraphy study and research in the real sense. She studied each and every Chinese writing scripts, such as the standard, cursive, seal, and clerical scripts, the scripts in large and small characters, etc. In terms of calligraphic styles, started on the firm foundation of Tie (calligraphy of rubbing), she also extended her practice to include Northen Wei’s stele inscriptions, calligraphy on bamboo slips and silk, covered from model calligraphic works of Jin and Tang to those of Ming and Qing dynasty. After absorbing and learning from strong points and advantages of various caliigraphers, she finally developed her own style.

中国当代书法家中,周慧珺肯定是大师级的书法家,可是令人不解的是,整个书坛似乎知道她的人好像不多。这可能是她为人低调的缘故吧。

周慧珺是浙江镇海人,出生于一九三九年十二月。她曾经担任中国书法家协会副主席,上海市文联副主席、上海市书法家协会主席。现为中国书法家协会与上海市书法家协会名誉主席。

周慧珺生长在一个翰墨飘香的商人家庭,从小就操笔练字。酷爱书画艺术的父亲对女儿周慧珺的学习生活并不是很关心,而是任其自由发展。不幸的是,她年轻时就患上了严重的类风湿关节炎,原先灵活的关节变得迟滞、酸痛,给她练习书法带来很大的障碍。但是,她反而练书法炼得更苦更勤。

1974年,周慧珺创作了《行书字帖——鲁迅诗歌选》,在一年之内四次重版,印数超过百万册,创下了新中国毛笔书法字帖发行数量的新纪录。有读者说,细读这本字帖,无论如何也不能相信这是一位病魔缠身的弱女子书写的。逆境中的周慧珺终于走了出来,取得了巨大的成功。

从小学书的她,父亲要她学赵孟頫,可是她独爱米南宫。1975年,周慧珺进入了上海中国画院,成为专业书法家。此时的她,如渴骥奔泉,开始了真正意义上的对书法的探索。真、草、篆、隶,大字榜书、蝇头小楷,无所不涉。并把取法范围不断地扩大,在学帖的基础上,广临了北魏碑版、简牍帛书。上溯晋唐、下及明清。博采众长,形成了自己的风格。

.