Tsue Da Tee (Cui Dadi, 1903 – 1974) was born in Beijing and trained as a teacher. However, he believed that life is about living and living is experiencing, so he left China in 1937 to travel extensively in the Southeast Asian countries and eventually settled in Singapore in 1946.

Since young, he developed a strong liking for the Chinese calligraphy and practiced extensively various calligraphic styles. His constant search for knowledge led him to visit London in 1953. While there he found the opportunity to do research in Chinese calligraphy, especially the oracle bone inscriptions at the British Museum. He also held several calligraphy exhibitions in London and Paris.He left London in 1958 and headed for Penang where he spent several years to focus on refining his calligraphic skills. While he did not teach calligraphy in Penang, he had definitely left a mark there. Today, inscribed sign-boards with calligraphy written by him can still be seen at many places in Penang. In 1965, he finally returned to Singapore and devoted the rest of his time to teaching and promotion of the Chinese calligraphy. He was the volunteer calligraphy teacher of the Calligraphy Society of the Hua Yi Secondary School. He also held many exhibitions of his works in Singapore and Malaysia.

Since young, he developed a strong liking for the Chinese calligraphy and practiced extensively various calligraphic styles. His constant search for knowledge led him to visit London in 1953. While there he found the opportunity to do research in Chinese calligraphy, especially the oracle bone inscriptions at the British Museum. He also held several calligraphy exhibitions in London and Paris.He left London in 1958 and headed for Penang where he spent several years to focus on refining his calligraphic skills. While he did not teach calligraphy in Penang, he had definitely left a mark there. Today, inscribed sign-boards with calligraphy written by him can still be seen at many places in Penang. In 1965, he finally returned to Singapore and devoted the rest of his time to teaching and promotion of the Chinese calligraphy. He was the volunteer calligraphy teacher of the Calligraphy Society of the Hua Yi Secondary School. He also held many exhibitions of his works in Singapore and Malaysia.

In his teaching of Chinese calligraphy, it was almost a rule to start with the Wei stele, followed by zhuan (official seal style), kai (regular) and then walking and cursive styles. All the work books were appropriately selected by him for students according to their progress in learning, personality and character. In this way, the students could fully develop their own potentials and characteristics.

To many of those who are followers of the art of Chinese Calligraphy in Singapore and the surrounding region, the mention of Tsue Da Tee evokes deep respect and admiration for a man who was well known for his calligraphy.

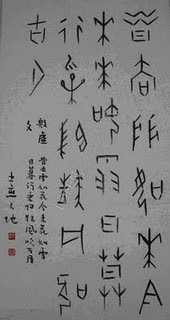

He was one of those rare calligraphers in Singapore and Malaysia who were skilful in many calligraphic styles, such as kai (regular), li (clerical), cao (cursive), zhuan (official seal), bronze and oracle bone inscriptions. In addition, he was not afraid of experimenting and opening new grounds in the calligraphic art. His beautiful and controlled brushwork – the dense sweeping strokes bearing the characteristic twists and turns – were skilfully executed with intent to express the underlying meaning and emotion of each character or form. He was truly a prolific artist and his works are noted for their vitality, strength, grace and beauty.

Some of his students who are well known calligraphers in Singapore include Yong Cheong Thye (Yang Changtai) and Goh Yan Kee (Wu Yaoji).

It is rare to find someone in Singapore who earned his living as a professional calligrapher, and Tsue was one. It is a pity that his works are not systematically studied and preserved.

.

崔大地(1903-1974)出生于北京,是一名受训教师。然而,他相信生命就是生活,生活就是体验,所以他于1937年离开了中国,尽情游览东南亚各国,并于1946年来到新加坡。

他于1958年离开伦敦,前往槟城,勤练书法。在槟城期间,他并没有收学生,但那里肯定在留下了他的书法痕迹。今天,他写的招牌匾额,在槟城还是随时可见。1965年,他终于回到新加坡定居,把剩余的时间放在书法教学与推广上面。他担任过华义中学书法会的义务书法导师。他也在新马举办了不少的书法展。

崔先生教导学生时,多数先学隶书,然后学魏碑、篆书、楷书及行草各种书体。学生所临摹的碑帖,都是经过精心挑选,并依个别学生的进度、性格与风格作适当的选择。因此,学生们都能各自发挥己长,发展自己的个人风格。

对那些关注新加坡与这一地区书法发展的人来说,提到崔大地的书法,必然令人肃然起敬。

在新马,他是少数精通各体书法的书法家之一,楷、隶、草、篆、钟鼎文、甲骨文,样样皆精。同时,他也不怕进行新的尝试,为书法开辟新道路。他美丽而又控制的书法线条,具有特色的扭与转,熟练地表达了每一个字与形式所要透露的意思与情感。他是个多产的书家,作品有活力刚强、优雅美丽。

他的一些学生如今在书法界有名气的包括:杨昌泰与吴耀基。

在新加坡,以书法为生的专业书法家不多见。崔大地就是这样的一个。很可惜他的书法没有被有系统的整理与学习。